Media Capture in Russia: An Expensive Venture

A Financial Analysis of Key Russian Media Companies

Introduction

Stock phrases such as “Russia is not an aggressor,” “Ukraine is a puppet of the West,” “Russia is defending itself against the collective West,” and “Russia is seeking peace” are just a few examples of Russian propaganda that a significant portion of the population continues to repeat.

As Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine persists, a battle is being fought far from the trenches: in the offices of media outlets, on air, in newspaper articles, on news websites, and on social media.

The newly implemented war censorship laws[1] and increased repressions[2] make propaganda the only permitted, reportable, and acceptable “truth” in Russia. As the country’s ranking on the World Press Freedom Index[3] continues to decline, the Kremlin’s propaganda is yielding tangible results.

Reports indicate that Russian state-controlled media have been using disinformation techniques to justify the all-out war against Ukraine since 2014[4]. As a result, the majority of Russia’s population is drowning in confusion, with simultaneous support of and opposition to the war[5]. This confusion, along with wartime censorship, stifles political activity, and the authorities face no substantial anti-war movement or resistance[6]. Consequently, the Kremlin continues its invasion.

This report aims to unpack the components of Russia’s propaganda machine. Part of a research project whose goal is to cover both the “top” of media ownership and the “bottom” of consumption, this study covers the former.

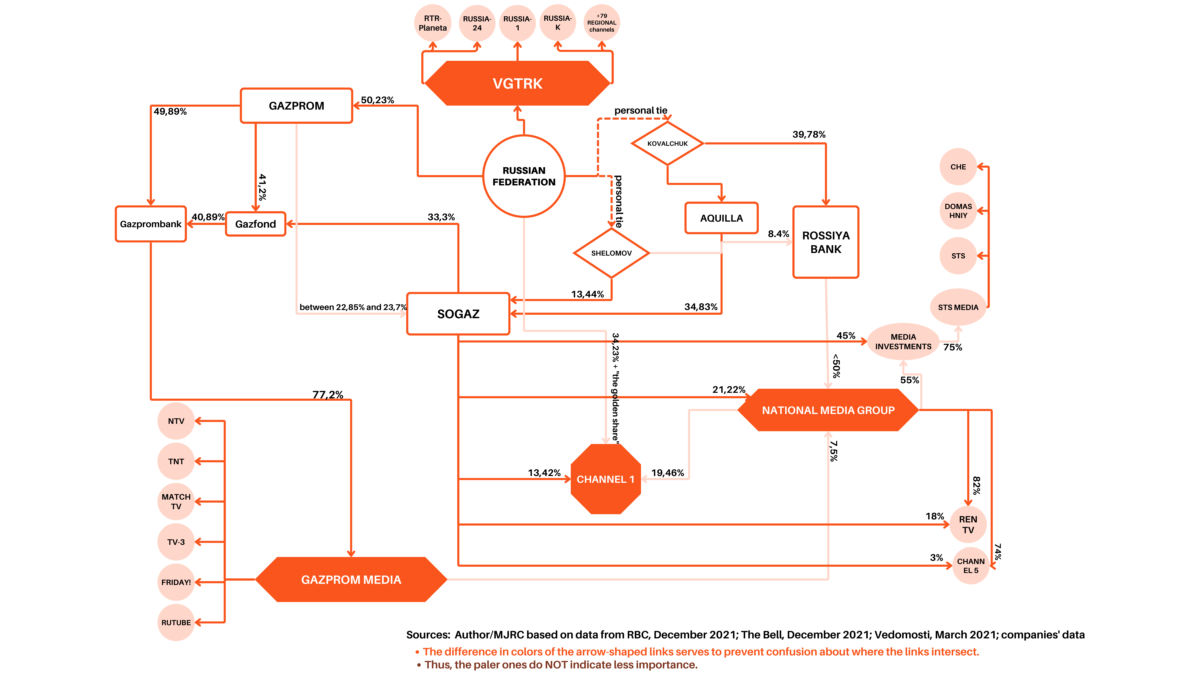

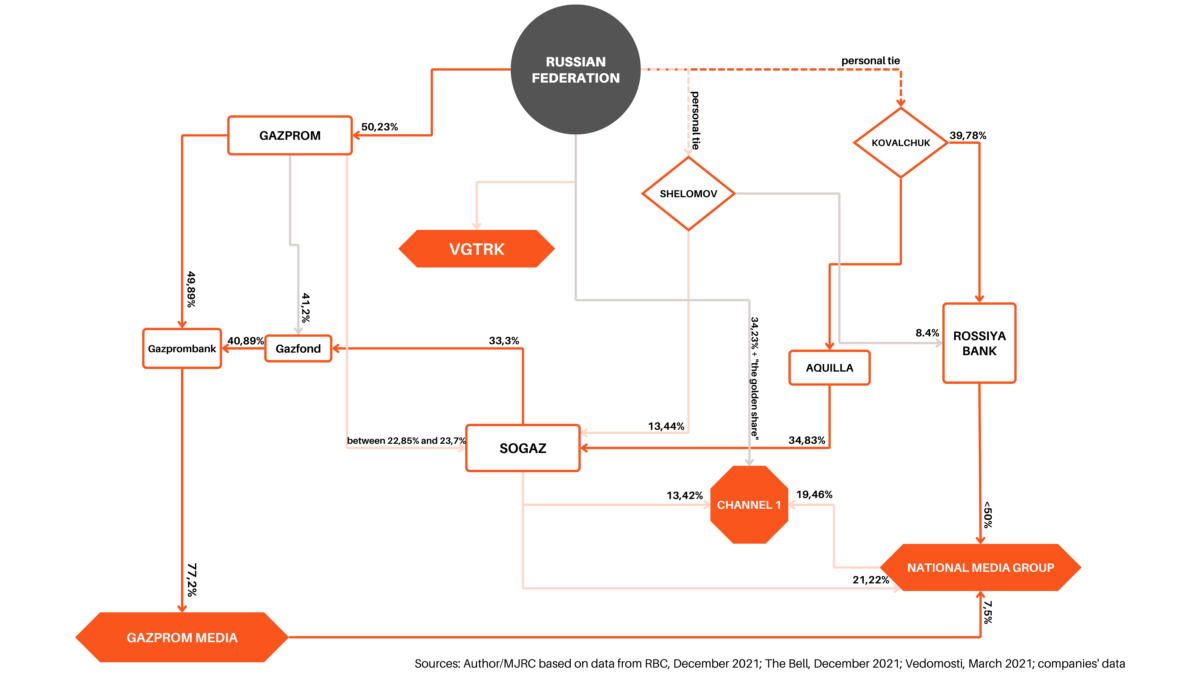

The report analyzes three media giants in Russia: Gazprom Media Holding, National Media Group, and VGTRK (the All-Russian State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company). They are key players in the Russian media sphere, securing control of the mass audience in Russia. By presenting their ownership connections and the corruption involved in their operations, the analysis aims to describe the main elements of the Russian media capture model.

The report uses data from the holdings’ financial records for the past few years, including information about their revenue, net profit, and capital. It looks at what the full-scale war effort brought into the media sector: namely, more state subsidies and intensified propaganda. The report also profiles the key players at the helm of these media companies, using information from extensive investigative work carried out by journalists.

Although these companies perform poorly on paper in financial terms, their ties with the Kremlin and the corruption surrounding them give them access to immense wealth that helps propel their operations in a political system where nepotism and cronyism are blatant.

The Media Ownership Puzzle

The ownership structures of the three holdings studied in this report do not allow for any maneuvering. Their assets are either owned by the government or by Vladimir Putin’s close circle. This means that the Kremlin controls both the flow of money, with billions in the pockets of the President’s chosen people, and the narrative. The ownership structures are murky, but data collected from journalistic reporting, investigative work, and the companies’ limited public records shows that they are interconnected, with the government remaining the ultimate beneficiary.

Before delving into the ownership maps and the Kremlin’s involvement, it is important to emphasize that television remains the primary source of information for Russians. According to polls by Levada Center[7], 63% of those surveyed in May 2022[8] said that television was their primary news source. The federal authorities continue to pour money into television channels and tighten their control over them. The main assets of the three largest media conglomerates analyzed in this report are their television channels.

In 2009, Presidential Decree № 715 established a list of “All-Russian Mandatory Public Television and Radio Channels” that would be included in the First Digital Multiplex, a package of free and universally available television and radio channels[9]. The decree was part of a national program aimed at providing digital television signal to the population, with a budget amounting to RUB 122.5bn (US$ 1.5bn)[10] from 2009 to 2015. Out of the ten television channels in the first multiplex, eight are tied to state ownership and the three media holdings analyzed (Gazprom Media Holding, National Media Group, and VGTRK). Five of those channels belong to VGTRK, a state-run broadcaster.

In 2012, Roskomnadzor, a federal agency responsible for censoring the media, finalized the list of winners for the Second Multiplex package. TV Rain (Телеканал «Дождь»), an independent news channel covering politics, business and culture, still broadcasting via satellite and cable at the time, applied for a spot on the list but was not selected[11]. Over the years, the channel became the only opposition television source in Russia, working under pressure from the authorities. In 2022, it was forced to leave the country[12].

As a result, there are no politically independent television channels left in Russia neither within the universally available multiplex packages, nor through satellite or cable operators, nor digitally.

VGTRK

VGTRK, also known as the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company, is a state-run broadcast company with national, regional, and international television and radio channels. They include:

- National VGTRK TV Channels (First Multiplex): Russia-1 (Россия-1), Russia-24 (Россия-24), Russia-K (Россия-К), and Carousel (Карусель) – a joint project of Channel One and VGTRK

- International VGTRK TV Channels: RTR-Planet (РТР-Планета), and Russia 24 (Россия-24), which also broadcasts worldwide

- 79 regional TV channels/branches

- National Radio (First Multiplex): Radio Mayak (Радио Маяк), Radio of Russia (Радио России), and Vesti FM (Вести FM)

- Other Radio: Radio Youth (Радио Юность)

- 19 thematic channels for cable and satellite operations

- Digital: media platform SMOTRIM (СМОТРИМ, meaning “we are watching” in Russian), which brings together the content of all VGTRK’s assets; news portal VESTI.RU (ВЕСТИ.RU)

Gazprom Media Holding

Gazprom Media Holding is a joint stock company with 41 TV channels (including nationwide channels and packages of thematic and sports channels), six digital platforms, 12 content production and distribution entities, nine radio channels, eight print and online publications, and several others in advertising, services, and real estate. Its assets include:

- National TV Channels (First Multiplex): NTV (НТВ), Match TV (Матч ТВ)

- National TV Channels (Second Multiplex): TNT (ТНТ), TV-3 (ТВ-3), Friday! (Пятница!)

- Other TV Channels: NTV Plus: NTV Style (НТВ-Стиль), NTV Law (НТВ-Право), NTV Series (НТВ-Сериал), NTV HIT (НТВ-Хит); Match! sports channels: Match Premier (Матч! Премьер), Match! Arena (Матч! Арена), Match! Game (Матч! Игра), Match! Planet (Матч! Планета), Match! Football 1 (Матч! Футбол 1), Match! Football 2, Match! Football 3, KHL TV, KHL TV HD, Match! Fight (Матч! Боец), Horse World (Конный мир), Match! Country (Матч! Страна); Saturday! (Суббота!); TNT4 (ТНТ4); 2×2; Red Media TV channels: Kinohit, Kinokomediya, Kinomix, Kinopremiera, Kinosemya, Kinoseriya, Kinosvidaniye, Muzhskoe Kino, Nashe Novoe Kino, Indijskoe Kino, Rodnoe Kino, Kinouzhas, India, Kitchen TV, 365 Days TV, HDL, La Minor TV, Russian Night

- Digital platforms: RUTUBE, Yappy, PREMIER, 101.ru, NTV-Plus, Match Premier

- Radio: Radio Energy, Autoradio, Humor FM (Юмор FM), Comedy Radio, Children’s Radio (Детское радио), Like FM, Radio Romantika, Relax FM, Radio Zenit

National Media Group (NMG)

National Media Group (NMG) is a joint stock company that controls a 19.46% stake in Channel One[13], the main nationwide television channel in Russia, and a key propaganda tool that tops the First Multiplex. The state owns 34.23% of Channel One, along with “the golden share,” while VTB Bank, a majority state-owned bank, controls 32.89% of its shares, and Sogaz, an insurance company, holds a 13.42% stake. Other assets of National Media Group include:

- National TV Channels (Second Multiplex): REN TV (РЕН ТВ) where the NMG owns 82%, and Sogaz owns 18%; STS (CТС) and Domashniy (Домашний) that belong to STS Media, which the NMG owns through Media Investments company (Медиа Инвестиции). The NMG holds 55% of Media Investments, while Sogaz holds 45%. Media Investments control 75% of STS Media[14]

- Other TV Channels: Channel 5 (Пятый канал) – the NMG owns 74%, and Sogaz owns 3%; TV 78 (Телеканал 78); Che (Че), STS Love, STS Kids – belong to STS Media[15]

- Online video service: More.tv

- Digital platforms and newspapers: Newspaper Business Petersburg (Деловой Петербург); Private multimedia informational center Izvestia (Известия): IZ.RU portal, channel Izvestia, newspaper Izvestia, news services of REN TV, Channel 5, TV 78, and publication Business Petersburg; Website Sport-Express (Спорт-Экспресс)

- Paid TV: Media Telecom (Медиа-Телеком) – a joint venture of Rostelecom and National Media Group

The company also owns other assets in content production and distribution, advertising and digital production.

The structure described is only the tip of the iceberg. In reality, the outlets are mired in a more complicated thicket of links with state authorities, politicians, and businessmen.

VGTRK is a straightforward case, as it is owned by the government. On the other hand, Gazprom Media Holding and National Media Group have more opaque ownership structures. Despite being competitors, their ownership structures reveal connections with each other and the government. One such connection is billionaire businessman Yury Kovalchuk, who is known to be Putin’s crony. Kovalchuk holds a significant stake in Sogaz, Russia’s largest insurance company by revenue.

According to investigative project Proekt, Kovalchuk is “the likely second most influential person in the country.”[16] He is a co-owner of Bank Rossiya, also known as “Putin’s Bank,” which has grown into a business empire during Putin’s rule. Bank Rossiya is also implicated in the financial revelations of the Panama Papers[17]. Bank Rossiya holds a stake in National Media Group although its exact size is unknown. It does not exceed 50%, according to RBC[18].

The Bell reported that Kovalchuk also holds the largest share of Sogaz through his company Aquilla, which belongs to him, his wife, and the top executives of Bank Rossiya[19]. The second-largest shareholder of Sogaz is Gazprom, a state-controlled conglomerate[20]. Additionally, 13.44% of Sogaz is held by Mikhail Shelomov, who is Putin’s relative[21].

Sogaz, in turn, holds a 33.3% share of Gazfond, Gazprom’s pension fund, and the second-largest shareholder of Gazprombank, one of Russia’s three largest banks[22]. Gazprombank, in turn, controls Gazprom Media[23].

On the other hand, a stake of 21.22% of National Media Group is owned by Sogaz[24]. The insurance company also has shares in the Group’s other assets, including 13.42% of Channel One, 45% of Media Investments, 18% of REN TV, and 3% of Channel 5[25].

Finally, in 2016, Gazprom Media acquired[26] a 7.5% stake in National Media Group to collaborate on original content creation and distribution, and to share expertise[27].

A simplified map provides a clearer view of the Russian media ownership structure. The ownership circle consists of interconnected owners and is closed, with the government at the top and Yury Kovalchuk as the second most influential ownership figure. This structure appears locked within, with the state as the key beneficiary.

Financial Overview

VGTRK’s income has been on a downward spiral, with its 2022 revenue, a total of RUB 23.5bn (US$ 293m), being the lowest recorded in the last ten years. The company’s net profit has also experienced a decline. The company closed the year 2022 with a RUB 1.4-bn loss (US$ 17.5m), down from a RUB 1.5bn net profit (US$ 18.7m) in 2021. VGTRK’s capital was RUB 20bn (US$ 250m) in 2022.

Regarding Gazprom Media Holding, the 2021 figures indicate revenue growth, with the company closing the year with RUB 382.8m (US$ 4.8m), up from RUB 290.8m (US$ 3.9m) in 2020. Gazprom Media’s net profit and loss figures remain in the billions, with a net profit of RUB 2.3bn (US$ 29m) in 2021. Losses in 2019 and 2020 were RUB 4.8bn (US$ 60m) and RUB 4.1bn (US$ 51m), respectively.

The reason why net profit exceeded revenue in 2021 was, according to a corporate report, the addition of Gazprom Media’s “income from participation in other organizations,” a total of RUB 3.6bn (US$ 45m). The company’s capital continued to rise and amounted to almost RUB 127bn (approximately US$ 1.6bn) in the same year.

According to the latest available data, National Media Group pulled in revenues of RUB 47.2bn (US$ 589m) in 2021, an increase from RUB 41bn (US$ 512m) in 2020. As for National Media Group’s net profit, it has tended to decline. The company netted RUB 9m (US$ 112,000) in 2020, which was a significant drop from RUB 1.5bn (US$ 18.7m). In 2021, it reported net earnings of RUB 237m (US$ 3.9m), an improvement from the previous year.

According to the latest data available, Channel One’s revenue in 2021 showed signs of recovery after the 2020 result, which was the lowest revenue in ten years at RUB 25.2bn (US$ 299.8m). Channel One closed in 2021 with RUB 28bn (US$ 347m) in revenue. As for the company’s net profit, the last ten years have been tumultuous, with billion-ruble losses from 2013 to 2019. However, 2020 was its best year, with a net profit of RUB 6.3bn (US$ 78m). In 2021, its net profit was much lower at RUB 581m (US $7.2m).

Based on the financial data available, the three Russia-based media conglomerates analyzed in this report generated a revenue of approximately RUB 751.6bn in the decade ending in 2021, which is almost US$9bn at current prices. It is presumed that Channel One’s books are kept separately from National Media Group, which owns a stake in the channel. Historically, VGTRK and Channel One have been leading in revenue generation, but in recent years (2020-2021), National Media Group has surpassed the other two companies in terms of revenue size.

When considering profitability, the three companies collectively lost RUB 4bn (US$ 47.6m) over the decade ending in 2021. Among them, Channel One experienced the largest loss by far. Gazprom Media Holding is another company that incurred losses, but its reported revenues are significantly lower than the others, suggesting that the company may be subsidizing its media division through revenues from other businesses, or that its financial records do not accurately reflect its financial situation.

The profitability data provide a strong indication of the significant losses that Russian media giants have recently experienced. Over the decade ending in 2021, the annual average combined loss of the three media players (including Channel One’s books as a separate figure) was RUB 400.1m (US$ 4.76m) at current prices. In the five years leading up to 2021, that figure increased to RUB 428.2m (US$ 5.1m) at current prices. While these figures alone may not represent a large amount for the Kremlin’s purse, the addition of state budget allocations that these companies receive provides a more accurate picture of the financial predicament these companies have been facing.

In recent years, the declining financial performance of the media companies analyzed in this report has been partly due to the worsening ad market, especially in the context of the war.

The three media groups have a strong foothold in the advertising market thanks to their joint ad sales strategy. In 2016, VGTRK, Gazprom Media, National Media Group, and Channel One (as a separate entity) founded the National Advertising Alliance, a limited liability company. Each of the four companies holds a 25% stake in it[28]. The Alliance controls 95% of all television ad sales in Russia[29].

Over the last few years, the country’s advertising market has stagnated, as demonstrated by the Alliance’s key financial indicators (see below). The four holdings have repeatedly changed the Alliance’s leadership but failed to bolster growth[30]. The latest blow to Russia’s advertising market is the withdrawal of investments by western companies following the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. This has resulted in a reported loss of 30-40%, which is not yet reflected in financial reports. In October 2022, the Alliance announced a 20-30% increase in prices for television advertising[31].

Wartime Television: State Subsidies, Propaganda, and Audience Reactions

The Russian government’s funding flow into the media sector increased over the years. In 2011, RUB 61.1bn (US$ 741.4m) of the federal budget went into the media; in 2015, that number reached RUB 82.1bn (US$ 996.2m), going as high as RUB 121.1bn (US$ 1.5bn) and RUB 114bn (US$ 1.4bn) in 2020 and 2021 respectively[32].

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 led to a further increase in government spending in the media. According to records from Russia’s finance ministry cited by the Moscow Times, some RUB 17.4bn (US$ 211.1m) from the federal budget was allocated to the media sector in January-March 2022[33]. This amount was 3.2 times higher than the January-March spending of RUB 5.4bn (US$ 65.5m) in 2021[34]. In March 2022 alone, when the war effort had fully begun, the government spent RUB 11.9bn (US$ 144.4m) to finance propaganda[35].

According to the federal budget plan for 2023, Russia will provide a total of RUB 119.2bn (US$ 1.4bn) to support the media sector[36]. Subsidies amounting to RUB 25.8bn (US$ 313m) will be allocated to VGTRK, while Channel One will receive two rounds of subsidies, of RUB 6bn (US$ 72.8m) and RUB 269m (US$ 3.3m)[37]. In addition to those, there are collective support packages of RUB 147m (US$ 1.8m) and RUB 8.3bn (US$ 100.7m) for Channel One, VGTRK, NTV, and several other television and radio channels[38].

State money comes with state-approved content orders, which the companies and their television channels must obey. As a result, there have been cuts to entertainment programs and an expansion of news and political content in recent years. Russia-1 has increased the airtime of Olga Skabeeva’s propagandist show “60 Minutes” and brought back the political propaganda show “Who’s Against?”[39]. The news programs on Channel One have become longer, while NTV is reportedly considering temporarily strengthening its socio-political content at the expense of its landmark detective series and entertainment shows.[40]

Despite the increased spending, there are tentative indications that the Russian audience may be growing tired of wartime propaganda on television. According to a study conducted by research holding Romir, there has been a downward trend in the amount of time Russians spent watching TV between February and July 2022[41]. Although Channel One and Russia-1 remain the most popular, their average daily reach has decreased from 33.7% to 25.5% for the former and from 30.9% to 23% for the latter[42]. NTV has lost its position as the “third most popular” television channel, as its reach decreased from 21.1% to 16.3%[43]. REN TV was slightly ahead with a reach of 16.6%[44]. Meanwhile, Romir reports that the usage of Telegram, a popular messenger app in Russia, has increased from 19.1% to 26.8%[45].

However, the above indicators should be viewed with caution. According to political sociologist Maksim Alyukov, who was interviewed by Meduza regarding Romir’s study, Russia is still a country that heavily relies on television[46]. Romir’s figures do not provide a guarantee of a significant shift in television consumption among Russians. Further research is necessary.

The Anatomy of Media Capture in Russia: Nepotism, Cronyism, and Corruption

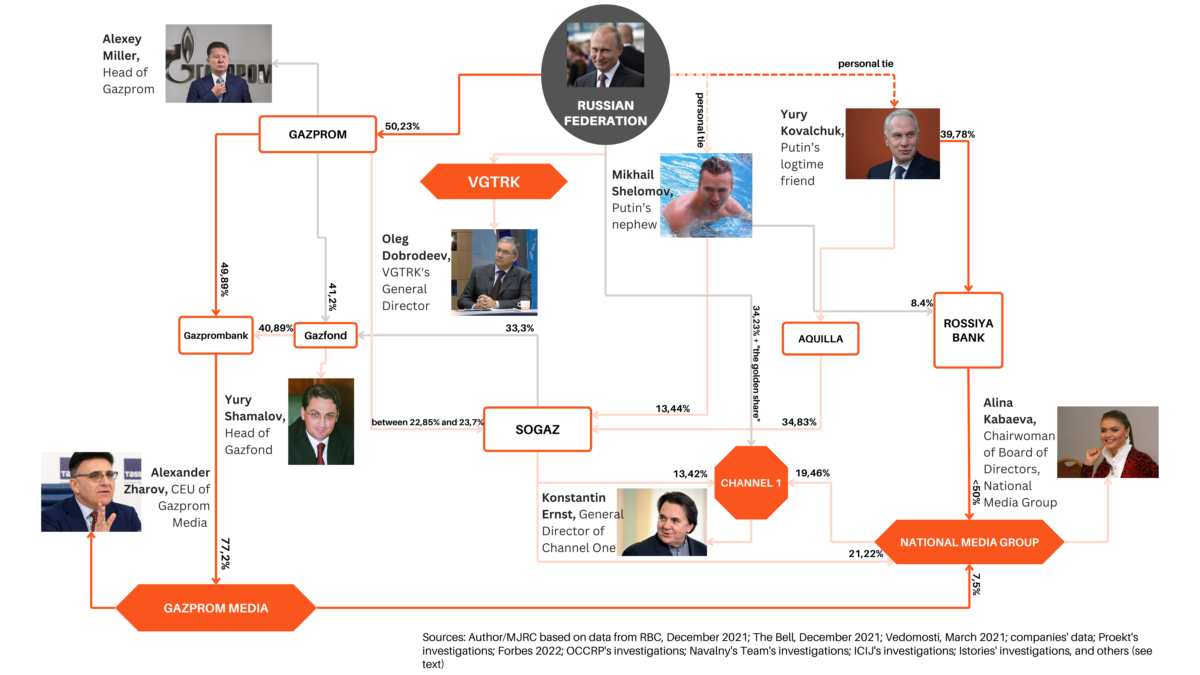

In order to comprehend the mechanisms of capture within the Russian media, it is necessary to conduct an in-depth analysis of the individuals who control or manage the largest media groups in the country. The Russian state has solidified its control over the public narrative during the Putin regime through a network of individuals with business interests in state-run companies, as well as direct and indirect connections to the Kremlin (very often family ties). The following is a summary of the key individuals involved in the overall scheme of Russian media capture.

Yury Kovalchuk has known Putin since the 1990s when he was Putin’s neighbor at the infamous country house cooperative Ozero [The Lake], which was notorious for how quickly its members’ wealth grew during Putin’s rule. Kovalchuk is a co-owner of Bank Rossiya. Proekt cites a 2006 report which states that Kovalchuk acquired the bank’s largest share at the beginning of Putin’s second presidential term[47]. When the US government sanctioned Kovalchuk in 2014, it referred to him as Putin’s “close advisor” and “personal banker.”[48]

The Panama Papers revealed that offshore schemes connected with Putin’s cronies were carried out through Bank Rossiya[49]. A more recent investigation drew from leaked emails of the LLCInvest domain, which showed that a network of more than 80 entities (companies and nonprofits) holds “assets worth at least US$ 4.5bn, including mansions, business jets, yachts, and bank accounts filled with cash.”[50] Bank Rossiya owns some of the assets directly, while others are owned indirectly through the bank’s shareholders, including Kovalchuk[51].

Formally, Putin was never connected to Bank Rossiya. However, as Proekt’s investigation has shown, the alleged mother of his third daughter, Svetlana Krivonogikh, holds a 2.8% share of Bank Rossiya through a firm named Relax[52]. This is one more connection amid numerous others, including Putin’s confirmed daughter, Katerina Tikhonova, who married Kirill Shamalov, son of Nikolay Shamalov, another Bank Rossiya shareholder and Putin’s longtime friend[53].

Yury Kovalchuk and his family’s fortune amounts to US$ 2.6bn[54]. Kirill Kovalchuk, Yury Kovalchuk’s nephew, is the President of National Media Group[55].

Alexey Miller has been the head of Gazprom since 2001. He worked for Putin in the 1990s at the mayor’s office in St. Petersburg where his job was reportedly to collect bribes[56]. By now, he is a billionaire. A recent investigation by Navalny’s Team has connected the dots regarding Miller and his family’s real estate. The team found that Miller’s family owns property worth RUB 43bn (US$ 534m)[57]. Navalny’s Team uncovered the scheme behind Miller’s corruption, having exposed multiple offshore maneuvers.

Mikhail Shelomov is Putin’s nephew. As Proekt reported, Shelomov is a former construction worker and photographer. His wealth grew suddenly as Putin became President. Shelomov’s company Aksept acquired a 13.5% share of insurance company Sogaz in 2004[58]. His 3.9% share in Bank Rossiya (also through Aksept) became known in the bank’s 2005 report[59], and the stake later increased to 8.4%[60].

According to a 2017 investigation by OCCRP, for the last ten years, Shelomov worked at state company Sovkomflot where the average yearly salary was around US$ 8,400[61]. However, journalists approximated his acquired assets as worth US$ 573m by 2017, while his company Aksept showed no commercial activity[62]. Proekt’s 2019 approximation of his fortune is US$ 1.25bn, which is a striking contrast with Shelomov’s tilted and old wooden house in the village of Zarechie in the Moscow region[63].

Yury Shamalov is the older son of Nikolay Shamalov, Putin’s old friend and a member of the country house cooperative Ozero [The Lake] (mentioned above in Kovalchuk’s context). He is the brother of Kirill Shamalov, the ex-husband of one of Putin’s daughters. Yury Shamalov worked for Putin and Miller in the 1990s in St. Petersburg[64]. Since 2003, he has been the head of Gazfond, a large pension fund, and is on the board of directors at Gazprom Media Holding[65]. Not much is known about Shamalov’s wealth except for his property on Rublevo-Uspenskoe Highway, which is the most expensive (and an elite-targeted) place to live in Russia[66].

Konstantin Ernst has been leading Channel One as its General Director since 1999. The Pandora Papers revealed Ernst’s involvement in a billion-dollar business deal. An offshore company of which he became a shareholder post-2014 Sochi Olympics “held a 23% interest in a Russian company, which bought 39 aging but valuable Soviet-era cinemas and surrounding property from the city of Moscow.”[67]

The reports show that a government-organized auction was orchestrated in favor of the partnership with Ernst’s involvement. His offshore company had received a US$ 16m loan from a bank in Cyprus, which is partly owned by VTB Bank, Russia’s state-controlled bank[68]. Eventually, the deal proceeded, and the cinemas were sold at half their value and taken down to build shopping malls despite the locals’ public objections[69]. With irremovable Ernst in leadership – and exactly when he closed that very offshore deal – Channel One was experiencing billion-ruble losses.

Oleg Dobrodeev has been the head of VGTRK since 2000, first, as Chairman, and then as General Director from 2004 onwards. Proekt’s 2020 investigation revealed that Dobrodeev’s family owns real estate worth RUB 1.7bn (US$ 21m).[70] Proekt emphasizes that the state media company VGTRK has been experiencing billion-ruble losses over the last several years, and there are no public records of Dobrodeev’s income.

Alexander Zharov became CEO of Gazprom Media in 2020[71], having previously served as Head of Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor) since 2012[72]. However, according to Novaya Gazeta, under Zharov’s leadership, Roskomnadzor was turned from “a boring regulator of communications” into “the main censorship body in Russia.”[73]

Some of the key developments during Zharov’s tenure included extrajudicial website blocking, a ban on LinkedIn, lobbying for the “sovereign Internet’ law, and multiple failures in executing blocking orders (such as the popular messenger Telegram, which was never successfully blocked despite Roskomnadzor’s persistent attempts)[74].

Alina Kabaeva, a former rhythmic gymnast and Olympic champion, became Chairwoman of the board of directors at National Media Group in 2014[75]. According to The Insider, her salary in 2018 amounted to RUB 785m (US$ 9.7m)[76], despite the company’s loss of RUB 453m in the same year.

Kabaeva is rumored to be Putin’s mistress and the mother of his children, with reports about their relationship dating back to 2008[77]. Proekt’s recent investigation revealed that Kabaeva owns and/or personally controls approximately US$ 120m worth of real estate, including numerous apartments, a penthouse, several houses, and a villa[78]. These assets were allegedly acquired through Putin’s close circle, with Yury Kovalchuk, mentioned earlier in the report, being a part of it[79].

Conclusions

Russia’s three media giants, Gazprom Media Holding, National Media Group, and VGTRK, are interconnected through an ownership structure where the state remains the primary beneficiary. Shareholding links and the Kremlin’s personal ties demonstrate how the Russian media landscape is captured through a closed and tightly controlled structure characterized by nepotism, cronyism, and corruption.

The primary media assets of the three holdings and the state are television channels, including Channel One, Russia-1, Russia-24, Russia-K, Carousel, NTV, Match TV, TNT, TV-3, Friday!, REN TV, STS, and Domashniy. These channels are the most popular sources of media content for most Russians. Unfortunately, there are no politically independent television channels remaining in Russia.

The major media companies are continuously losing money due to the stagnating advertising market and the withdrawal of western capital. Meanwhile, the government is providing support to the media by giving away billions of rubles. The state budget indicates that media sponsorship is increasing, with wartime as an incentive for more funding.

The channels receive generous subsidies, but with all the state money comes the Kremlin’s order to produce more propaganda. The channels obediently follow this order, which results in an increase in political programs and a decrease in entertainment. As a result, there are emerging indications that the Russian population may be getting tired of wartime television.

Billions of rubles from the state budget will continue to be allocated towards propaganda television, but this will come at the expense of other state-funded sectors. Will the government be willing to cut social support programs in the near future to be able to fund media instead? Only time will tell. However, one thing is abundantly clear: those in control of the three holdings analyzed in this report (and Channel One, minority owned by one of the three) have been unable to guide the companies towards steady growth, even prior to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

It is unknown whether Russians will continue to switch off television propaganda programs. What might be easier to predict, however, is the future business performance of the Russian media companies. Russia is heading towards a drastic economic decline caused by Western sanctions, loss of foreign investments, continuous military overspending, and ubiquitous corruption. This decline is likely to lead to more predicaments for media companies in the country.

[1] “Russia Criminalizes Independent War Reporting, Anti-War Protests,” Human Rights Watch, 7 March 2022, available online at

https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/03/07/russia-criminalizes-independent-war-reporting-anti-war-protests (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[2] “Антивоенное дело. Инфографика уголовного преследования за антивоенную позицию” (Anti-war cases. Infographics of criminal prosecution for the anti-war position), Ovdinfo, available online at https://data.ovdinfo.org/antivoennaya-infografika?_gl=1*1hd8tyd*_ga*OTc0MTAxNjIyLjE2ODMyMTY2MDY.*_ga_J7DH9NKJ0R*MTY4MzIxNjYwNS4xLjEuMTY4MzIxNjYxOC40Ny4wLjA(accessed on 3 May 2023).

[3] “2023 World Press Freedom Index – journalism threatened by fake content industry,” Reporters Without Borers, RSF.org, available online at https://rsf.org/en/2023-world-press-freedom-index-journalism-threatened-fake-content-industry?data_type=general&year=2023 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[4] “Narrative Warfare: How the Kremlin and Russian news outlets justified a war of aggression against Ukraine,” Atlantic Council, available online at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/narrative-warfare/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

[5] Svetlana Erpyleva, “«Раз начали, заканчивать нельзя»: Как меняется отношение россиян к войне в Украине” (“Since [we] started it, there is not way [we] end it”: How the attitude of Russians to the war in Ukraine is changing), Re:Russia, 14 March 2023, available online at https://re-russia.net/expertise/060/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

[6] Svetlana Erpyleva, “How the attitude of Russians to the war…,” cit.

[7] Non-governmental research organization labeled as a “foreign agent” in Russia.

[8] “Источники информации: Москва и Россия” (Information sources: Moscow and Russia), Levada-Center, 15 July 2022, available online at https://www.levada.ru/2022/07/15/istochniki-informatsii-moskva-i-rossiya/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

[9] “УКАЗ Президента РФ от 24.06.2009 N 715” (Decree of the President of the Russian Federation from 24 June 2009 N 715), Document.kremlin.ru, available online at https://web.archive.org/web/20130502094705/http://document.kremlin.ru/doc.asp?ID=53066&PSC=1&PT=3&Page=1 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[10] “ФЦП «Развитие телерадиовещания в Российской Федерации на 2009–2015 годы»” (Federal Target Program (FTP) “Development of TV and radio broadcasting in the Russian Federation for 2009-2015”), Digital.gov.ru, available online at https://digital.gov.ru/ru/activity/programs/4/?utm_referrer=https%3a%2f%2fwww.google.com%2f (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[11] “Телеканал «Дождь» не попал во второй цифровой мультиплекс” (TV channel “Rain” did not get into the second digital multiplex), Forbes, 14 December 2012, available online at https://www.forbes.ru/news/231002-roskomnadzor-obyavil-uchastnikov-vtorogo-tsifrovogo-multipleksa (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[12] “Телеканал “Дождь”, прекративший работу в начале войны, начал вещание за границей” (TV channel “Rain,” which stopped working at the beginning of the war, began broadcasting abroad), BBC News Russian Service, 18 July 2022, available online at https://www.bbc.com/russian/news-62212858 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[13] “ВТБ и «Согаз» станут акционерами «Первого канала»” (VTB and Sogaz will become shareholders of Channel One), Vedomosti, 22 March 2021, available online at https://www.vedomosti.ru/media/articles/2021/03/22/862542-vtb-i-sogaz-stali-aktsionerami-pervogo-kanala(accessed on 15 April 2023).

[14] “Какими медиа владеют новые собственники VK. Инфографика” (What media belong to the new owners of VK. Infographics), RBC, 4 December 2021, available online at https://www.rbc.ru/technology_and_media/04/12/2021/61aa4d7a9a7947ead936d92a (accessed on 5 April 2023).

[15] “What media belong to the new owners of VK…,” cit.

[16] “Портрет Юрия Ковальчука, второго человека в стране” (Portrait of Yuri Kovalchuk, the second person in the country), Proekt.media, 9 December 2020, available online at https://maski-proekt.media/yury-kovalchuk/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

[17] Olesya Shmagun, Denis Dmitriev, Miranda Patrucic, and Ilya Lozovsky, “Mysterious Group of Companies Tied to Bank Rossiya Unites Billions of Dollars in Assets Connected to Vladimir Putin,” OCCRP, 20 June 2022, available online at

https://www.occrp.org/en/asset-tracker/mysterious-group-of-companies-tied-to-bank-rossiya-unites-billions-of-dollars-in-assets-connected-to-vladimir-putin (accessed on 11 May 2023).

[18] “What media belong to the new owners of VK…,” cit.

[19] Petr Mironenko, “«Газпром» и Ковальчук в VK, неожиданное решение ОПЕК+ и Enron 20 лет спустя” (Gazprom and Kovalchuk in VK, an unexpected decision by OPEC + and Enron 20 years later), The Bell, 2 December 2021, available online at https://thebell.io/gazprom-i-kovalchuk-v-vk-neozhidannoe-reshenie-opek-i-enron-20-let-spustya (accessed on 17 March 2023).

[20] Mironenko, “Gazprom and Kovalchuk in VK…,” cit.

[21] Mironenko, “Gazprom and Kovalchuk in VK…,” cit.

[22] “Gazprombank (Joint Stock Company),” United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, available online at https://www.unepfi.org/member/gazprombank-joint-stock-company/ (accessed on 19 May 2023).

[23] Mironenko, “Gazprom and Kovalchuk in VK…,” cit..

[24] “What media belong to the new owners of VK,” cit.

[25] “What media belong to the new owners of VK,” cit.

[26] Kseniya Boletskaya, “«Газпром-медиа» купил 7,5% акций «Национальной медиа группы»” (Gazprom-Media bought a 7.5% stake in National Media Group), Vedomosti, 31 March 2916, available online at https://www.vedomosti.ru/technology/articles/2016/03/31/635878-gazprom-media-natsionalnoi-media-gruppi (accessed on 20 May 2023).

[27] “”Газпром-медиа” купил часть “Национальной медиа группы”” (Gazprom-Media bought a part of National Media Group), BBC News Russian Service, 31 March 2016, available online at https://www.bbc.com/russian/news/2016/03/160331_gazprommedia_nmg_share (accessed on 20 May 2023).

[28] “Крупнейшие российские медиахолдинги объединились для продажи рекламы” (The largest Russian media holdings united to sell advertising), Kommersant, 4 July 2019, available online at https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3030187 (accessed on 9 June 2023).

[29] “ООО «Национальный рекламный альянс»

Company profile” (LLC “National advertising alliance” Company profile), Kommersant, 25 August 2021, available online at https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4957185 (accessed on 9 June 2023).

[30] “Телеканалы меняют главного продавца эфирной рекламы” (TV channels change the main seller of on-air advertising), Vedomosti, 1 August 2019, available online at https://www.vedomosti.ru/technology/articles/2019/08/01/807795-telekanali-menyayut-glavnogo-prodavtsa-efirnoi-reklami (accessed on 9 June 2023).

[31] Dmitry Ignatiev, “Главный селлер ТВ-рекламы НРА объявил о повышении цен в 2023 году” (Leading TV Ad Seller National Advertising Alliance Announces Price Increases in 2023), Vedomosti, 26 October 2022, available online at https://www.vedomosti.ru/media/articles/2022/10/27/947562-glavnii-seller-tv-reklami-obyavil-o-povishenii-tsen (accessed on 9 June 2023).

[32] “Краткая ежегодная информация об исполнении федерального бюджета (млрд. руб.)” (Brief annual information on the execution of the federal budget (billion rubles)), Russia’s Ministry of Finance, 12 May 2023, available online at https://minfin.gov.ru/ru/statistics/fedbud/execute?id_57=80041-kratkaya_ezhegodnaya_informatsiya_ob_ispolnenii_federalnogo_byudzheta_mlrd._rub (accessed on 8 June 2023).

[33] “Миллиарды на пропаганду. Расходы бюджета на госСМИ подскочили втрое на фоне войны” (Billions for propaganda. Budget spending on state media tripled amid the war), The Moscow Times Russian Service, 12 April 2022, available online at https://www.moscowtimes.ru/2022/04/12/milliardi-na-propagandu-rashodi-byudzheta-na-gossmi-podskochili-vtroe-na-fone-voini-a19511(accessed on 8 June 2023).

[34] “Billions for propaganda. Budget spending on state media…,” cit.

[35] “Billions for propaganda. Budget spending on state media…,” cit.

[36] “Приложение 15. Распределение бюджетных ассигнований по разделам, подразделам, целевым статьям (государственным программам Российской Федерации и непрограммным направлениям деятельности), группам видов расходов классификации расходов федерального бюджета на 2023 год и на плановый период 2024 и 2025 годов” (Annex 15. Distribution of budget allocations by sections, subsections, target items (state programs of the Russian Federation and non-program areas of activity), groups of types of expenditures of the classification of federal budget expenditures for 2023 and for the planning period of 2024 and 2025), Federal Law No. 466-FZ of December 5, 2022 “On the federal budget for 2023 and for the planning period of 2024 and 2025”, available online at https://base.garant.ru/405874129/7af06a18e696b1f1f06e05ebdce27796/ (accessed on 8 June 2023).

[37] “Annex 15. Distribution of budget allocations by sections…,” cit.

[38] “Annex 15. Distribution of budget allocations by sections…,” cit.

[39] “Как россияне смотрели телевизор в 2022 году. Инфографика” (How Russians watched TV in 2022. Infographics), RBC, 7 December 2022, available online at https://www.rbc.ru/technology_and_media/07/12/2022/638f2ce79a79474841ee0985 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

[40] “How Russians watched TV in 2022…,” cit.

[41] “Ромир: Как изменилось медиапотребление россиян c февраля 2022” (Romir: How Russian media consumption has changed since February 2022), Romir, 19 August 2022, available online at https://romir.ru/studies/kak-izmenilos-mediapotreblenie-rossiyan-c-fevralya-2022(accessed on 8 June 2023).

[42] “Romir: How Russian media consumption has changed…,” cit.

[43] “Romir: How Russian media consumption has changed…,” cit.

[44] “Romir: How Russian media consumption has changed…,” cit.

[45] “Romir: How Russian media consumption has changed…,” cit.

[46] “Аудитория российских телеканалов резко сократилась. Люди устали от пропаганды? Неужели они будут меньше смотреть телевизор?” (The audience of Russian TV channels has drastically decreased. Are people tired of propaganda? Will they watch less TV?), Meduza, 29 August 2022, available online at https://meduza.io/episodes/2022/08/29/auditoriya-rossiyskih-telekanalov-rezko-sokratilas-lyudi-ustali-ot-propagandy-neuzheli-oni-budut-menshe-smotret-televizor (accessed on 10 June 2023).

[47] “Portrait of Yuri Kovalchuk, the second person in the country…,” cit.

[48] John Hyatt, “Генерал дезинформационной войны. Юрий Ковальчук – ближайший соратник Путина, отвечающий за тотальную пропаганду. Кто он?” (General of the disinformation war. Yuri Kovalchuk is Putin’s closest associate, in charge of all-out propaganda. Who is he?), Forbes, 21 March 2022, available online at https://forbes.ua/ru/richest/khto-shepoche-na-vukho-putinu-21032022-4871 (accessed on 12 May 2023).

[49] “Россия: Влиятельный банкинг” (Russia: Powerful banking), OCCRP and Novaya Gazeta, 9 June 2016, available online at https://www.occrp.org/ru/panamapapers/rossiya-putins-bank/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).

[50] Shmagun, Dmitriev, Patrucic, and Lozovsky, “Mysterious Group of Companies Tied to Bank Rossiya…”, cit.

[51] Shmagun, Dmitriev, Patrucic, and Lozovsky, “Mysterious Group of Companies Tied to Bank Rossiya…”, cit.

[52] “Расследование о том, как близкая знакомая Владимира Путина получила часть России” (An investigation into how Vladimir Putin’s close friend got a part of Russia), Proekt.media, 25 November 2020, available online at https://maski-proekt.media/tainaya-semya-putina/ (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[53] “Russia: Powerful banking,” cit.

[54] “Forbes Profile: Yuri Kovalchuk & family,” Forbes, 30 May 2023, available online at https://www.forbes.com/profile/yuri-kovalchuk/?sh=4ae5c86d1aae (accessed on 30 May 2023).

[55] “Portrait of Yuri Kovalchuk, the second person in the country…,” cit.

[56] “”Он просто писал сумму во время беседы.” Бизнесмен Максим Фрейдзон рассказывает о коррупционных схемах, в которых участвовал Путин, союзе КГБ и бандитов” (“He just wrote down the amount during the conversation.”Businessman Maxim Freidzon talks about corruption schemes in which Putin participated, the KGB’s alliance, and bandits), Radio Liberty, 23 May 2015, available online at https://archive.ph/Jsugi (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[57] “Путин. Миллер. Газпром” (Putin. Miller. Gazprom), Miller.navalny.com, available online at https://miller.navalny.com (accessed on 23 May 2023).

[58] Mariya Zholobova, “Портрет Михаила Шеломова, племянника президента, обладателя миллиарда долларов и туалета во дворе” (Portrait of Mikhail Shelomov, the president’s nephew, owner of a billion dollars and a toilet in his yard), Proekt.media, 30 October 2019, available online at https://www.proekt.media/portrait/mikhail-shelomov/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[59] Mariya Zholobova, “Portrait of Mikhail Shelomov…,” cit.

[60] “Личный миллионер президента” (The president’s personal millionaire), OCCRP, 24 October 2017, available online at https://www.occrp.org/ru/putinandtheproxies/relative-wealth-in-russia/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[61] “The president’s personal millionaire,” cit.

[62] “The president’s personal millionaire,” cit.

[63] Mariya Zholobova, “Portrait of Mikhail Shelomov…,” cit.

[64] “Расследование РБК: как строит бизнес семья Шамаловых” (RBC investigation: How the Shamalov family builds a business), RBC, 17 December 2015, available online at https://www.rbc.ru/investigation/business/17/12/2015/567179f69a794796318770aa (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[65] “Окружение Путина, Бизнес, Госкомпании: Юрий Шамалов” (Putin’s circle, Business, State-owned Companies: Yury Shamalov), Rublevka.proekt.media, available online at https://rublevka.proekt.media/person/shamalov-yuriy-nikolayevich (accessed on 24 May 2023).

[66] “Putin’s circle, Business, State-owned Companies: Yury Shamalov,” cit.

[67] “The Power Players: Russia, President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle, Konstantin Ernst, CEO of Channel One Russia,” ICIJ, available online at https://projects.icij.org/investigations/pandora-papers/power-players/en/player/konstantin-ernst (accessed on 24 May 2023).

[68] “The Power Players: Russia, President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle…,” cit.

[69] Roman Anin, “Эрнст, офшоры и кино” (Ernst, offshores, and cinema), Istories.media, 3 October 2021, available online at https://istories.media/investigations/2021/10/03/ernst-ofshori–i-kino/ (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[70] “Семья главы ВГТРК Олега Добродеева владеет недвижимостью на Рублевке стоимостью 1,7 млрд рублей. Один из домов куплен у разыскиваемого по обвинению в мошенничестве” (The family of VGTRK’s Head Oleg Dobrodeev owns real estate on Rublyovka worth 1.7 billion rubles. One of the houses was bought from a man wanted on fraud charges), Proekt.media, 4 February 2020, available online at https://www.proekt.media/article/dobrodeev-rublevka/ (accessed on 21 May 2023).

[71] “Leadership, Board of Directors, Alexander Zharov,” Gazprom-Media, available online at https://www.gazprom-media.com/en/about/leadership?leader=1007 (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[72] “«Ведомости» и РБК сообщили об уходе главы Роскомнадзора в «Газпром-медиа». Александр Жаров заявил, что ничего об этом не знает” (Vedomosti and RBC announced the departure Roskomnadzor’s Head to Gazprom-Media. Alexander Zharov said he did not know anything about it), Meduza, 12 February 2020, available online at https://meduza.io/news/2020/02/12/vedomosti-i-rbk-soobschili-ob-uhode-glavy-roskomnadzora-v-gazprom-media-aleksandr-zharov-zayavil-chto-nichego-ob-etom-ne-znaet (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[73] Anastasiya Torop, “Ваш милый цензор: Как Александр Жаров выстроил из Роскомнадзора главный цензурный орган в стране” (Your sweet censor: How Alexander Zharov built the main censorship body in the country out of Roskomnadzor), Novaya Gazeta, 26 March 2020, available online at https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2020/03/26/84516-vash-milyy-tsenzor (accessed on 25 May 2023).

[74] Anastasiya Torop, “Your sweet censor…,” cit.

[75] “Алина Кабаева возглавила совет директоров “Национальной медиа группы”” (Alina Kabaeva became the head of the board of directors of National Media Group), Vedomosti, 30 September 2014, available online at https://www.vedomosti.ru/management/news/2014/09/30/alina-kabaeva-vozglavila-sovet-direktorov-nacionalnoj-media (accessed on 20 May 2023).

[76] Sergey Ezhov, “Миллиарды вокруг Кабаевой. Сколько близкие к Путину олигархи платят непризнанной первой леди” (Billions around Kabaeva. How much the oligarchs close to Putin pay the unrecognized first lady), The Insider, 24 November 2020, available online at https://theins.ru/korrupciya/236997 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

[77] Mikhail Maglov, Roman Badanin, Mikhail Rubin, and other Proekt’s journalists, “Рассказ о том, как вассалы Владимира Путина обеспечили царскую жизнь Алины Кабаевой и ее детей, а спецслужбы скрыли существование этой семьи от всей страны” (The story of how Vladimir Putin’s vassals ensured the royal life of Alina Kabaeva and her children, and the secret services hid the existence of this family from the whole country), Proekt.media, 28 February 2023, available online at https://www.proekt.media/guide/alina-kabaeva-putin/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

[78] Maglov, Badanin, Rubin, et. co., “The story of how Vladimir Putin’s vassals…,” cit.

[79] Maglov, Badanin, Rubin, et. co., “The story of how Vladimir Putin’s vassals…,” cit.

This report was fully sponsored by the Central European University Foundation of Budapest (CEUBPF). The ideas presented herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of CEUBPF.

Invest in independent media research and join a community of practice.

Your contribution supports MJRC’s investigations and global analysis. As a supporter, you can receive early access to new findings, invitations to small-group briefings, inclusion in our Supporters Circle updates, and the option to be listed on our Supporters Page.

Contribute to MJRC