Media in Exile: Key Players in Resisting Autocratization

Investigator: Simone Benazzo, ULB

On 13 April 2023, El Faro, a Salvadorian media outlet, announced that it had taken a decision with far-reaching consequences. After operating for a quarter of a century in its home country, the newsroom has chosen to register in Costa Rica as a non-profit Fundación Periódica, citing “the dismantling of democracy, the lack of counterbalances to the exercise of power by a small group of people, the attacks on press freedom and the disappearance of all mechanisms of transparency and accountability” as the factors that led it to take this step.

El Faro is unlikely to feel alone in Costa Rica.

Four Nicaraguan newspapers and investigative bodies – Confidencial, La Prensa, Nicaragua Actual, Onda Local – have already found refuge there, as the Ortega regime’s increasing repression prevented them from continuing their work in acceptable conditions of safety.

The experience of these Central American media is just one chapter in a book that seems to be getting longer by the day.

While journalism in exile is nothing new in itself, with examples dating back to at least the 18th century, recent decades have seen a surge in media that have set up, or been founded, outside their national borders.

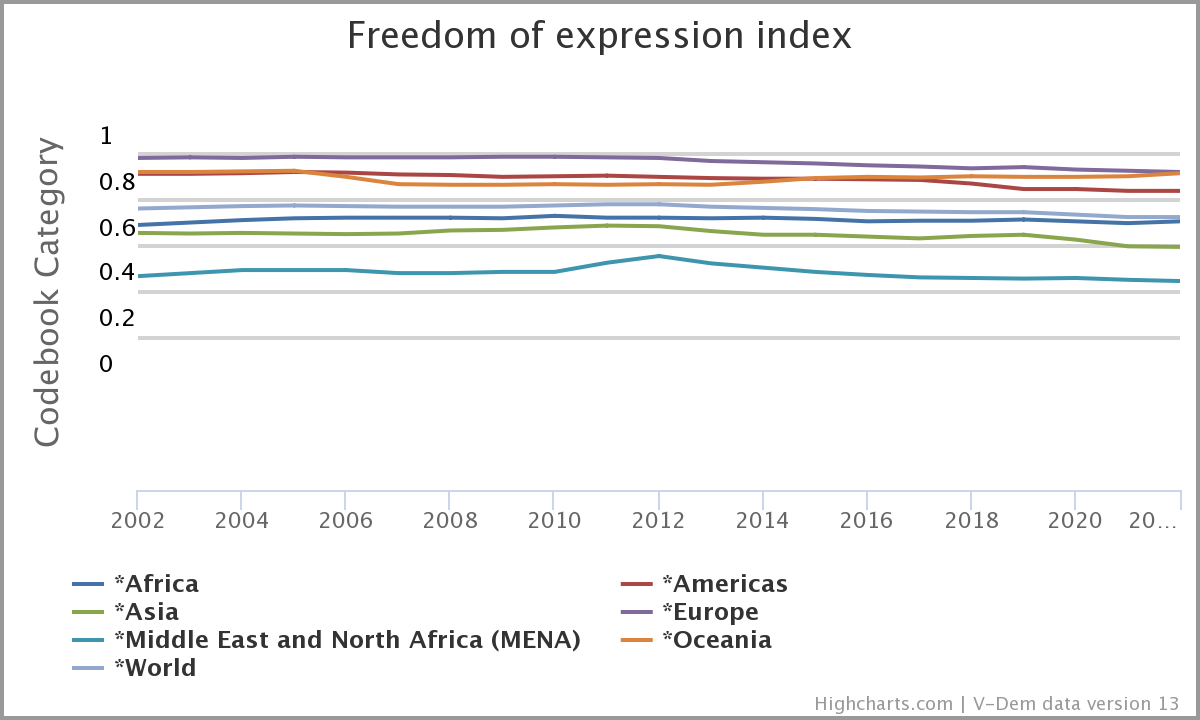

This phenomenon is the logical flip side of the large-scale deterioration in freedom of expression that has affected every region of the world – with the exception of Oceania – since 2012, according to Vdem data. Last year saw a record number of journalists imprisoned (CPJ 2022).

Even if no precise data still exists on the subject of media in exile, not least because experts do not necessarily employ the same terminology, international observers have not missed the trend.

RSF reports having earmaked 70% of the financial grants its Assistance Desk has provided since January 2022 for supporting journalists in exile, and having written more than 400 letters to support visa or asylum applications by journalists who had to flee their country. Similarly, in 2022 CPJ helped 206 journalists to find shelter abroad, compared to 63 that were helped in 2020.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 triggered a new wave of media emigration, which did not spare prestigious traditional publications such as Novaya Gazeta Europe and The Moscow Times. This watershed event put the media in exile in the spotlight, with coverage appearing in both the mainstream media, such as The New York Times and The Financial Times, and the specialist media press – Global Investigative Journalism Network, Columbia Journalism Review, NiemanReports.

The importance of the media in exile is, indeed, hard to underestimate. As Christophe Deloire, RSF secretary-general, put it, their impact “reaches beyond the borders of their country of origin at a time of globalised challenges to the provision of news and information and propaganda wars.”

However, the new interest in the subject among the general public and practitioners has highlighted a glaring lack of in-depth academic studies on the subject.

Filling the gap and contributing to policy-making

As is also clear from the short list of sources at the bottom of the page, most academic research has focused exclusively on individual journalists in exile or has failed to distinguish between them and the media in exile, addressing the phenomenon of ‘exile journalism’ as a whole. No studies have been devoted to exile media as actors in their own right, whose challenges, needs and ambitions differ to a large extent from those of individual, mostly freelance, journalists.

Most of the information we have on the work of media in exile comes from independent reports published by media freedom NGOs and other social actors working to support journalism around the world (see the “Non-academic sources” section at the bottom of the page).

This project represents therefore the first academic attempt to systematize the multi-layered phenomenon of media in exile by collecting and organizing first-hand data. It is led by Simone Benazzo, PhD student at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), with the support of the Media and Journalism Research Centre (MJRC).

Besides contributing to increase academic knowledge on the subject, the project aims to encourage policy-makers in the EU and other like-minded partners to support newsrooms in exile by better understanding their necessities and the fundamental role they play in the campaign to defend liberal democracy worldwide.

As the recent example of Russian media in exile makes clear, these media outlets are a key player in the global effort to resist autocratization and reverse democratic backsliding. Russian media in exile such as Meduza have been at the forefront of campaigns to debunk Kremlin-fuelled disinformation about what Russian citizens are presented as a “special military operation” in Ukraine.

Beyond Russia, the well-established networks of Belarusian, Iranian and North Korean media in exile, for example, often provide the only reliable and verified information about what is happening within the largely closed borders of their countries. The rapidly growing network of Turkish media in exile, and many other newsrooms in autocratic countries as diverse as Eritrea, Syria, Nicaragua and Myanmar, are increasingly playing a similar pivotal role.

What’s more, as the world of journalism as a whole struggles to come to terms with hugely disruptive technologies such as AI, a number of newsrooms in exile have already started experimenting with these tools to improve the quality of the journalism they produce and circumvent the strict censorship measures that autocratic governments have put in place to deny their domestic audiences access to evidence-based reporting and critical voices (see Rowan 2023 below).

Mapping media in exile: a multifaceted scenario united under the same mission

Preliminary research for this project identified around one hundred media in exile (see chart below for detailed data).

They vary in size, scope, numbers of countries covered, staff, values, outreach, financial solidity, revenue streams, audience, popularity and in several other dimensions.

Yet, they all share the same mission: holding the power accountable from abroad, when reporting in the home country – or region – is no longer feasible because of threat of any sort, from smear campaign to intimidation, from physical attacks on employees and premises to hostile takeover.

Despite the many challenges the condition of exile abroad entails (psychological burden, homesickness, financial problems, difficulties in adjusting to a new culture, a new work environment, often a new language), their very existence proves they have chosen not to cave in.

Media in exile (by world region)

Photo by Matt Popovich on Unsplash

Sources

Academic sources

Arafat, R. (2021). Examining Diaspora Journalists’ Digital Networks and Role Perceptions: A Case Study of Syrian Post-Conflict Advocacy Journalism. Journalism Studies, 22(16), 2174–2196. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1990110

Balasundaram, N. (2019). Exiled Journalists as Active Agents of Change: Understanding Their Journalistic Practices. In I. S. Shaw & S. Selvarajah (Eds.), Reporting Human Rights, Conflicts, and Peacebuilding (pp. 265–280). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10719-2_16

O’Loughlin, C., & Schafraad, P. (2016). News on the move: Towards a typology of Journalists in Exile. Observatorio (OBS*), 10(1). https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS1012016869

Porlezza, C., & Arafat, R. (2021). Promoting Newsafety from the Exile: The Emergence of New Journalistic Roles in Diaspora Journalists’ Networks. Journalism Practice, 0(0), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1925947

Sarıaslan, K. Z. (2020). This is not journalism: mapping new definitions of journalism in German exile. (ZMO Working Papers, 25). Berlin: Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO). https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2020072713154300695462

Shumow, M. (2014). Media production in a transnational setting: Three models of immigrant journalism. Journalism, 15(8), 1076–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884914521581

Skjerdal, T. S. (2010). How reliable are journalists in exile? British Journalism Review, 21(3), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956474810383773

(2011). Journalists or activists? Self-identity in the Ethiopian diaspora online community. Journalism, 12(6), 727–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911405471

Non-academic sources

Articles and reportages in specialized press

Dovbysh, O. & Rodina, E., Russian independent journalism in exile: In search of relevance and resilience, Russia.Post, 12 August 2022 (last accessed on 3 July 2023)

Hylton, A., Visions of Valeria, Columbia Journalism Review, 17 April 2023 (last accessed on 3 July 2023)

Katz Marston, C., Forced to Flee: How Exiled Journalists Hold the Powerful to Account, NiemanReports, 20 March 2023 (last accessed on 3 July 2023)

Parkhomenko, S., Russian independent media: Why they leave and why they stay, Russia.Post, 5 July 2022 (last accessed on 3 July 2023)

Philp, R., ‘Reporting from the Outside’: Lessons from Investigative Journalists in Exile, Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN), 9 May 2022 (last accessed on 3 July 2023)

Venkina, E., One Year in: How Putin’s war has changed journalism in exile, Deutsche Welle (DW), 16 February 2023 (last accessed on 3 July 2023).

Westcott, L., CPJ’s support to exiled journalists jumped 227% in 3 years, reflecting global press freedom crisis, Committee to protect journalists (CPJ), 16 June 2023 (last accessed on 3 July 2023)

Yablokov, I., Russia’s recently exiled media learn hard lessons abroad, Open Democracy, 6 December 2022 (last accessed on 3 July 2023)

Reports

Exile Journalism in Europe, Körber-Stiftung, 2022 (click here to download the report)

Forster, M. J., Outside: Exile News Media and reporting under threat, repression and reprisals, May 2019 (click here to download the report)

Hlinovská, A. & de Schutte, N. Independent Media in exile: a research report on challenges faced by independent media in exile, Free Press Unlimited, August 2021 (click here to download the report)

Mishra, T.P. Becoming A Journalist In Exile, Third World Media Network (TWMN), 2009 (click here to download the report)

Rebuilding Russian Media in Exile – Successes, Challenges and the Road Ahead, JX Fund, 29 November 2022 (click here to download the report)

Ristow, B., Independent Media in Exile, Centre for International Media Assistance (CIMA), June 2011 (click here to download the report)

Additional resources

European Parliament, REPORT on the protection of journalists around the world and the European Union’s policy on the matter (rapporteur: Isabel Wiseler-Lima), 2 June 2023 (2022/2057(INI))

Exile journalists map – fleeing to Europe and North America, Reporters Without Borders (RSF), 20 June 2023

Exile Journalism in Europe. Current challenges and initiatives at a glance. Körber-Stiftung

Faces of Exile, Committee to protect journalists (CPJ), 2008

Mugabo, L. E., Journalism in exile: lessons from Latin America and East Africa, online seminar at Reuters Institute (video available here)

Network of Exiled Media Outlets (NEMO)

DW Akademie, Space for Freedom

Invest in independent media research and join a community of practice.

Your contribution supports MJRC’s investigations and global analysis. As a supporter, you can receive early access to new findings, invitations to small-group briefings, inclusion in our Supporters Circle updates, and the option to be listed on our Supporters Page.

Contribute to MJRC